These Machines Can Put You in Jail

A million Americans a year are arrested for drunken driving, and most stops begin the same way:

flashing blue lights in the rearview mirror, then a battery of tests that might include standing on one foot or reciting the alphabet.

What matters most, though, happens next. By the side of the road or at the police station, the drivers blow into a miniature science lab that estimates the concentration of alcohol in their blood.

If the level is 0.08 or higher, they are all but certain to be convicted of a crime.

But those tests — a bedrock of the criminal justice system — are often unreliable, a New York Times investigation found.

The devices, found in virtually every police station in America, generate skewed results with alarming frequency, even though they are marketed as precise to the third decimal place.

Judges in Massachusetts and New Jersey have thrown out more than 30,000 breath tests in the past 12 months alone, largely because of human errors and lax governmental oversight. Across the country, thousands of other tests also have been invalidated in recent years.

Technical experts have found serious programming mistakes in the machines’ software.

States have picked devices that their own experts didn’t trust and have disabled safeguards meant to ensure the tests’ accuracy.

The Times interviewed more than 100 lawyers, scientists, executives and police officers and reviewed tens of thousands of pages of court records, corporate filings, confidential emails and contracts.

Together, they reveal the depth of a nationwide problem that has attracted only sporadic attention.

A county judge in Pennsylvania called it “extremely questionable” whether any of his state’s breath tests could withstand serious scrutiny. In response, local prosecutors stopped using them.

In Florida, a panel of judges described their state’s instrument as a “magic black box” with “significant and continued anomalies.”

Even some industry veterans say the machines should not be de facto arbiters of guilt.

“The tests were never meant to be used that way,” said John Fusco, who ran National Patent Analytical Systems, a maker of breath-testing devices.

Yet the tests have become all but unavoidable. Every state punishes drivers who refuse to take one when ordered by a police officer.

The consequences of the legal system’s reliance on these tests are far-reaching.

People are wrongfully convicted based on dubious evidence. Hundreds were never notified that their cases were built on faulty tests.

And when flaws are discovered, the solution has been to discard the results — letting potentially dangerous drivers off the hook.

A man backed his car into an 83-year-old woman outside a liquor store and then failed field sobriety tests.

Another man was stopped after vomiting out the window and veering “all over the road.”

One more driver, with a suspended license, was pulled over and blew a 0.32 — a level of drunkenness that would leave most people unconscious.

All three were arrested and charged with driving drunk.

All three had previous convictions for driving while intoxicated, according to police reports and court records.

And all three were acquitted after Massachusetts was forced to throw out their breath tests — along with more than 36,000 others — in one of the largest exclusions of forensic evidence in American history.

The Deerfield River snakes through the woods of northwestern Massachusetts, and on a hot Sunday in July 2013 it was packed with rafters.

Matthew Mottor arrived with more than a dozen friends and family members and two coolers of Blue Moon beer.

They spent hours tubing down the river and drinking before going ashore for a picnic.

That’s when a drunk woman in the group caught the eye of a Massachusetts State Police trooper patrolling the area.

The trooper, Steven Hean, told them to get their friend home.

The party over, Mr. Mottor left his girlfriend and got a ride to his truck, a few miles upriver.

He pulled his gray Dodge Durango onto the winding road.

He made it about 200 yards. Then he saw the flashing lights.

Trooper Hean wrote in a report that he stopped Mr. Mottor for driving 41 miles per hour in a 25 m.p.h. zone.

Detecting “a strong odor” of liquor on Mr. Mottor’s breath, the trooper asked him to perform some field sobriety tests, including walking heel-to-toe.

Accidents years earlier had left Mr. Mottor with metal plates in his ankles and feet, court records show.

“I explained to him that I’m not great at walking around on two feet on an everyday basis,” Mr. Mottor said.

After passing two tests — reciting the alphabet and standing on one leg — he struggled to walk in a line. Trooper Hean brought out his breath tester.

Hand-held devices, like Trooper Hean’s Alco-Sensor IV, contain fuel cells that react to the alcohol in exhaled breaths and generate an electric current — the stronger the current, the higher the alcohol level.

They are inexpensive and easy to maintain, but their results can be inconsistent.

Older women sometimes have trouble producing enough breath to get the machines to work. Toothpaste, mouthwash and breath mints — even hand sanitizer and burping — may throw off the test results.

Tests from those portable machines are not admissible in court in most states (California is among the exceptions).

But they often trigger an arrest, which leads to a test on another machine at the police station.

That result determines whether someone is charged — and, often, whether they’re convicted.

By the side of River Road, Mr. Mottor blew a 0.13, far above the legal limit. That’s when the cuffs came out.

Attempts to prevent drunken driving predate the modern automobile.

In the late 19th century, Britain had outlawed being drunk while operating a “carriage, horse, cattle or steam engine.”

In 1897, a London taxi driver named George Smith crashed his electric cab. He confessed to having had “two or three glasses of beer” and was fined 20 shillings.

It is widely regarded as the first arrest for intoxicated driving.

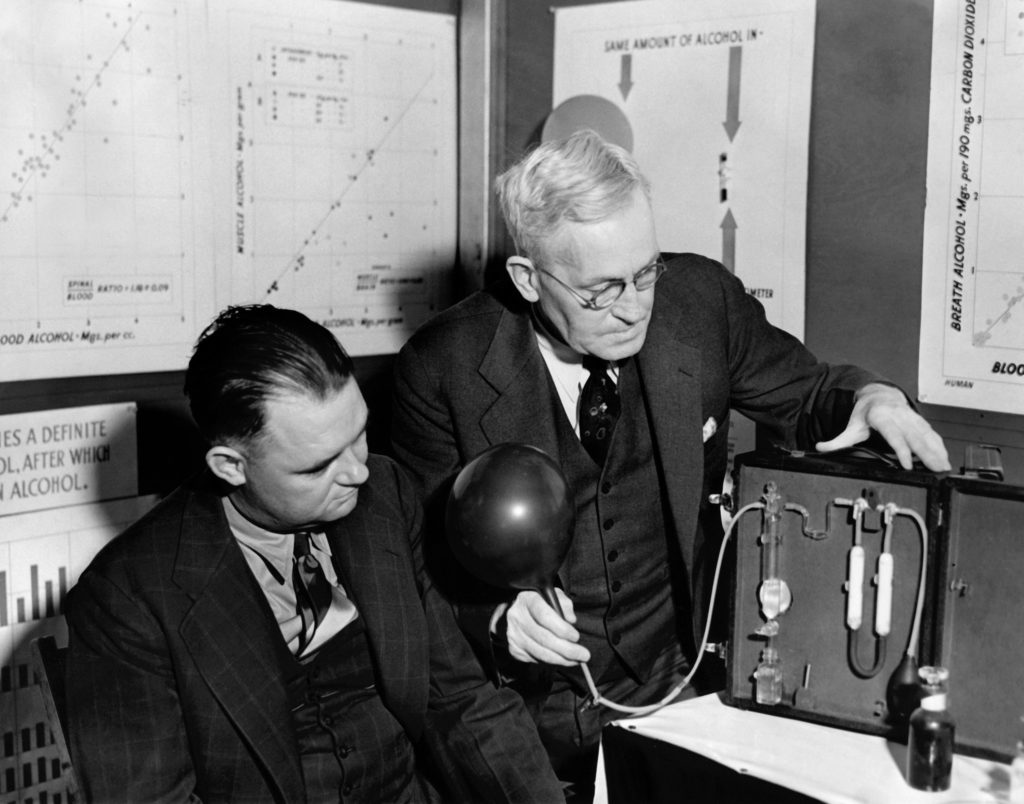

Near the end of Prohibition, a biochemist invented a suitcase-sized machine with vials of chemicals and a balloon to blow into.

Alcohol in the driver’s breath would trigger a reaction: the drunker the driver, the deeper the chemicals’ color.

It was called the Drunkometer.

But it was bulky and hard to use.

Two decades later, a police photographer and amateur chemist named Robert Borkenstein developed a similar but more portable machine.

He named it the Breathalyzer.

Police departments around the country bought Mr. Borkenstein’s invention and versions developed by competitors.

Then, in 1980, a fatal collision led to an overhaul of America’s drunken driving laws — and a sales boom for companies that made breath-testing devices.

Carime Lightner, 13, was walking to a church carnival in Fair Oaks, Calif., when a drunken driver slammed into her so hard she was knocked out of her shoes.

The man had been arrested repeatedly for intoxicated driving.

Carime’s mother started Mothers Against Drunk Driving and launched one of the most effective citizen lobbying campaigns in history.

States set stiffer penalties, including mandatory jail time in some cases, and made it illegal to drive with a blood-alcohol level above a designated mark.

The crackdown worked.

In 1982, the year the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration began keeping records, some 21,000 people were killed in drunken-driving incidents. The number of deaths tumbled to around 10,500

in the most recent annual tally, even as the number of miles driven by Americans has nearly doubled.

In most of the country, the threshold for illegal drunkenness is 0.08 grams of alcohol per 100 milliliters of blood.

The only way to measure that directly is to draw blood, which requires a warrant. Breath tests are simpler.

Testing machines can go for $10,000 or more, and some two dozen companies sell them in the United States.

The biggest contracts, with state police crime labs, are worth millions.

A St. Louis company, Intoximeters, made the portable device used on Mr. Mottor. Dräger, a German company, owns the rights to the Breathalyzer name.

CMI, based in Kentucky, is another industry leader.

“Our top priority is the quality and safety of our products,” said Brian Shaffer, a Dräger spokesman.

“Our products provide the highest level of forensic and legal integrity.”

He added, “Our advanced evidential breath alcohol testing instruments exceed the requirements of national and international regulatory agencies.”

CMI and Intoximeters did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Shirtless and still in swim trunks, Mr. Mottor arrived at the police barracks in Cheshire, Mass. He didn’t think he was drunk.

But he was starting to panic.

He had left his phone in his S.U.V. and had no way to tell his girlfriend what had happened.

He pictured her alone by the river, thinking he had driven into a ditch.

Mr. Mottor was escorted to the station’s breath-testing machine.

It was larger, more sophisticated and in theory more reliable than Trooper Hean’s portable instrument, and its results were admissible in court.

Trooper Hean asked Mr. Mottor to start blowing. Hoping it would help him get back to his girlfriend faster, he complied.

The Alcotest 9510, manufactured by Dräger, resembles a fax machine with a small hose.

As a person breathes into the device, a beam of infrared light is shot through the sample.

Chemicals, including the ethanol in alcoholic drinks, absorb light to varying degrees.

By analyzing how much light is absorbed, the instrument can identify the type of chemical and the amount of it present.

Many machines, including the Alcotest 9510, also use a fuel-cell sensor — the same type of tool that is in portable devices.

Each system is supposed to operate independently; if both return similar results, the theory goes, it’s an extra assurance that the measurement is accurate.

Mr. Mottor blew for about 10 seconds, the machine beeped, and a number flashed on its screen: 0.08.

He was charged with operating under the influence, which leads to the automatic revocation of driving privileges in Massachusetts.

Trooper Hean confiscated Mr. Mottor’s license and called a truck to tow his S.U.V.

Breath-testing machines need less than a minute to run their calculations.

What happens during those 60 seconds, though, has been the subject of years of courtroom fights.

Defense lawyers have repeatedly tried to forensically examine the machines, especially their software.

Inspecting the code could reveal any built-in flaws or assumptions the devices use in their calculations.

But even procuring a machine is a challenge. Manufacturers won’t sell them to the public.

Jan Semenoff, a former police officer who works with defense lawyers, was once a CMI salesman and had a machine left over from those days.

When he sent it in for a repair, CMI wiped the machine’s memory chip.

“They turned the damn thing into a paperweight,” Mr. Semenoff said.

Courts in at least six states, including New York, have rebuffed defense lawyers’ attempts to get their hands on the machines’ code.

But in 2007, the New Jersey Supreme Court granted a request by defense lawyers and ordered Dräger to allow outside experts to analyze the software for the Alcotest 7110 machines in use statewide.

The experts said it was littered with “thousands of programming errors,” according to their report to the court.

After reviewing the evidence, the court deemed the Alcotest 7110 “generally scientifically reliable.”

But the state court also acknowledged the devices had “mechanical and technical shortcomings” that had the potential to produce the wrong result.

Dräger said it quickly fixed the problems, but the state never rolled out the software update, court records show.

Dräger now advertises the 7110 as the only device on the market whose software “has been reviewed by independent third parties and approved by a Supreme Court decision.”

None of that made a difference in other states, which employ a variety of machines and standards.

Each state decides how rigorously it will test machines, and several have used devices that were deemed unreliable elsewhere.

In 2005, for example, Vermont’s toxicology lab scrutinized machines from four manufacturers.

The lab rated CMI’s Intoxilyzer 8000 as “unsatisfactory” and found that it gave inaccurate results on “almost every test,” according to a lab technician’s report.

But the same device was already being used in Mississippi, and it would soon be deployed by other states, including Ohio and Oregon.

Florida, too, adopted the Intoxilyzer 8000, even after a test machine short-circuited and started to smoke, state records show.

COURT RULING IN ORANGE COUNTY, FLA.

When the state began setting up its new devices, technicians found they were returning inaccurately low results, according to court testimony.

A CMI engineer diagnosed a problem with airflow, and he drilled a small hole in the exhaust valve to solve it.

The fix worked.

CMI started boring holes in all the devices it sent to police departments in Florida, court records show.

When defense lawyers discovered the undisclosed change, they challenged its legality.

The Collier County judge who heard the case in 2012 said he was “extremely concerned” about the modifications.

“A criminal defendant should not face conviction and possible incarceration based on secret undisclosed evidence,” he wrote in his ruling.

Ultimately, that case and others led several Florida judges to stop allowing breath tests to be used in their courtrooms.

Defense lawyers in state courts across the country have sought to learn more about the devices being used to convict their clients.

In two states, Washington and Massachusetts, they took aim at the instrument that Mr. Mottor blew into: Dräger’s Alcotest 9510.

When the State of Washington decided to spend more than $1 million to replace its aging machines in 2009, the state police chose the Alcotest 9510 despite a report by their own scientist that described the machines as “not yet ready for implementation.”

Before rolling out the machines, state officials debated whether to spend tens of thousands of dollars on an outside expert to evaluate the software.

Fiona Couper, a state toxicologist, emailed her colleagues: “I think we throw caution to the wind and proceed without paying up front for an independent evaluation.” (In an email to The Times, Ms. Couper said that “it was too premature to evaluate the software at that time.” Court records show no evaluation was ever done.)

In 2015, a local judge granted a request from defense lawyers to review the software underpinning the state’s Alcotest machines.

That task fell to a consulting company run by two veteran programmers and security experts, Robert Walker and Falcon Momot.

Mr. Walker had worked at Microsoft for more than a decade and was adept with Windows CE, the obsolete operating system powering the Alcotest 9510. Mr. Momot, a soft-spoken hacker with spiky facial piercings and a rainbow-colored mohawk, was known for his talent in hunting down complicated computer bugs and software vulnerabilities.

Dräger insisted on extraordinary security. It demanded that its software be reviewed on an isolated computer network and that the state police be able to inspect the testers’ equipment, according to court documents.

“I worked on the most confidential things that Microsoft does, and they don’t have any procedures like this,” Mr. Walker said in an interview.

After a couple weeks dissecting the Alcotest code, they wrote a nine-page draft report, “Defective Design = Reasonable Doubt.”

They planned to dig further, but things went awry when they shared their report with defense lawyers at a convention.

Dräger sent Mr. Walker a letter demanding that he and Mr. Momot ask anyone with a copy of their report to destroy it — including the lawyers who hired them — and to stay silent about the instruments’ inner workings.

Facing a giant company, Mr. Walker felt he had no choice but to comply. “I am an ant,” he said.

Mr. Shaffer, the Dräger spokesman, said the company was defending its intellectual property.

“We really have nothing to hide, but we have something to protect,” he said.

Although Mr. Momot and Mr. Walker’s preliminary report never made it into court, a few copies survived.

The Times obtained one from a defense lawyer.

FROM THE PRELIMINARY REPORT

The report said the Alcotest 9510 was “not a sophisticated scientific measurement instrument” and “does not adhere to even basic standards of measurement.”

It described a calculation error that Mr. Walker and Mr. Momot believed could round up some results.

And it found that certain safeguards had been disabled.

Among them: Washington’s machines weren’t measuring drivers’ breath temperatures. Breath samples that are above 93.2 degrees — as most are — can trigger inaccurately high results.

Washington had decided against spending more on a sensor that would check breath temperature and allow the software to adjust for it, according to Mr. Shaffer.

He said Washington wasn’t alone; most of Dräger’s American clients skip the sensors.

The Washington State Patrol is “very confident in the accuracy and reliability of the Dräger 9510 breath test instrument,” said Sergeant Darren Wright, a spokesman.

He added that the patrol did not believe that the breath temperature sensor was needed to produce accurate results.

Other states have disabled different safeguards.

In Minnesota, for example, officials found that the fuel-cell systems in their DataMaster devices often broke down, according to court testimony.

Instead of fixing the problem, technicians simply turned off that portion of the machine in 2012.

The effect was to eliminate an important quality-control check — one that had been a selling point when the machines were purchased.

The state’s Bureau of Criminal Apprehension, which manages the testing program, said it “remains confident in the reliability of results obtained by DataMaster devices across Minnesota.”

His license revoked, Mr. Mottor relied on rides from family and friends to get to the restaurant in the Berkshire Mountains where he was a chef.

The consequences rippled outward.

He and his girlfriend shelved plans to buy a house. He couldn’t sleep.

He could no longer drive his 2-year-old daughter to play dates.

He worried about going to jail and leaving his family unable to afford to heat their single-wide trailer.

“I think I took 10 years off my mother’s life,” Mr. Mottor said.

After three months, he was able to get his license reinstated while his case progressed.

Mr. Mottor hired a lawyer to fight the charges. To pay that bill, he maxed out his credit cards, raided his retirement fund and borrowed money from nearly everyone he knew.

His lawyer planned his defense: Mr. Mottor had been entrapped by the state trooper, his foot injury explained why he failed the field sobriety test, and a phenomenon called “retrograde extrapolation” meant that Mr. Mottor’s blood-alcohol level might have been lower when he was on the road than when he was tested at the police station.

It didn’t occur to either of them to question the breath-testing device itself.

Questioning the device worked for Robert Friedlander — and set off a chain reaction that destabilized Colorado’s enforcement of drunken-driving laws.

On the night of May 30, 2016, a Colorado State Patrol officer pulled Mr. Friedlander over after seeing his Audi sedan swerving.

At the station, he blew a 0.07 — below the threshold at which a driver is considered drunk, but high enough in Colorado for him to be charged with a lesser offense, impaired driving.

Mr. Friedlander, however, was adamant that he was not impaired — and that he had evidence to support his claim.

Years earlier, he had been convicted of impaired driving, and he had carried around a small portable breath tester ever since.

That May night, Mr. Friedlander had been drinking at the Ameristar casino in Black Hawk. He tested himself and blew a 0.05, he said.

Then, he said, he waited an hour, without drinking, before he hit the road.

As Mr. Friedlander fought the charges, his case uncovered widespread problems with how the state forensic lab had deployed its fleet of more than 160 new Intoxilyzer 9000s.

Before Colorado got those machines in 2013, a lab technician, Michael Barnhill, had tested devices from a number of manufacturers.

He testified in Mr. Friedlander’s case that his manager ordered him to destroy records from those tests, as well as the manual for the Intoxilyzers, in case defense lawyers tried to subpoena the materials.

The Colorado lab was rushing to meet its deadline to get the machines up and running.

But breath-testing devices are not operational right out of the box.

Each machine needs to be calibrated using samples with known alcohol concentrations.

The process can take an hour or more per machine.

Mr. Barnhill said lab records were faked to show that he had calibrated dozens of instruments that he had never touched.

And to speed things up, the lab’s supervisor summoned assistants, including an intern, a CMI lawyer and a sales manager, to help.

“I had taken apart equipment before, but, you know, with my father and whatnot,” the intern, Adam Lopez, said in a deposition.

“But never ever have I like done it on an instrument that is on a state level where it’s responsible for, you know, somebody’s prosecution.”

He added: “There probably were some errors here and there.”

MICHAEL BARNHILL’S DEPOSITION

In addition, the lab’s former science director said in a sworn affidavit that her digital signature had been used without her knowledge on documents certifying that the Intoxilyzers were reliable.

The lab kept using her signature after she left for another job.

The judge overseeing Mr. Friedlander’s case was appalled.

The lab decided to “consciously disregard truth and accuracy,” he wrote.

The judge ruled that Mr. Friedlander’s test was inadmissible unless the lab could prove its machine was producing sound results.

At that point, the prosecutor offered Mr. Friedlander a chance to plead guilty to the lesser charge of reckless driving. He took the deal.

Defense lawyers in Colorado seized on the ruling in Mr. Friedlander’s case to challenge breath test results in dozens of other cases.

Most courts followed the judge’s lead and excluded the tests, but there was no statewide resolution, according to local lawyers.

Any problems have “long since been resolved,” said Scott Bookman, the laboratory director at the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment.

“I am fully committed to transparency and accuracy, and we will operate with those chief principles at the forefront of everything we do.”

Mr. Friedlander, however, is skeptical.

“I don’t condone drunken driving in the least little bit, but I was trying to follow the law,” he said.

“The machines that they’re using really materially affect people, and these lab bureaucrats, running their little fiefdoms, didn’t seem to give a damn if they were accurate or not.”

Colorado wasn’t the only place where human mistakes caused a cascade of problems.

When Ilmar Paegle was hired to run the breath-testing program for the Metropolitan Police Department in Washington, D.C.,

his first order of business was to test its Intoxilyzers. Mr. Paegle, a retired United States Park Police officer, was stunned: Every machine was generating results that were 20 percent to 40 percent too high.

That discovery, in 2010, most likely meant that years of faulty tests had convicted innocent drivers.

Mr. Paegle’s predecessor, Kelvin King, who oversaw the program for 14 years, had routinely entered incorrect data that miscalibrated the machines, according to an affidavit by Mr. Paegle and a lawsuit brought by convicted drivers.

In addition, Mr. Paegle found, the chemicals the department was using to set up the machines were so old that they had lost their potency — and, in some cases, Mr. King had brewed his own chemical solutions. (Mr. King still works for the Metropolitan Police Department. A department spokeswoman said he was unavailable for comment.)

Mr. Paegle, believing the machines hadn’t been giving reliable results for at least a decade, pulled them out of service.

He alerted the city’s attorney general, whose office prosecuted drunken-driving cases.

The city stopped using breath-test results in new prosecutions, but it only acknowledged problems in cases going back 18 months.

The attorney general’s office determined that in that span, 350 people had been convicted based solely on results that were far too high.

Lawyers for those drivers were notified that their clients could ask to have their cases reopened.

LETTER TO DEFENDANTS IN WASHINGTON, D.C.

But more than 700 other people also had been convicted after receiving inflated test results.

The attorney general’s office didn’t believe those convictions hinged on the breath tests, so it decided not to notify those defendants that their results had been incorrect.

The reality, though, was that most of those 700-plus cases had ended in guilty pleas by defendants who thought, wrongly, that prosecutors had infallible scientific evidence that they were drunk.

As Mr. Mottor’s case inched along in Massachusetts, a parallel legal fight was playing out: Lawyers representing hundreds of drunken-driving defendants were pelting the state’s courts with requests for more information on the Dräger Alcotest 9510. (Their cases were consolidated into a single action.)

In 2016 — three years after Mr. Mottor was pulled over — the state’s highest court ruled that Massachusetts had to hand over two Alcotest machines.

The defense lawyers would be allowed to hire experts to test them.

The decision caused paralysis. Prosecutors froze thousands of cases until the review was finished.

The software experts and scientists who inspected the Alcotest 9510 machines found troubling mistakes, according to their reports to the court.

In some circumstances — when the devices’ two testing methods produced substantially different results, for example — the machines were supposed to generate error messages and terminate the test.

Instead, the devices printed a result. (Dräger blamed an error by its computer programmers, which it said has now been fixed.)

But the machines weren’t the only problem. The Massachusetts forensic lab, which for years had been plagued by scandals over faked drug test results and tampered evidence, lacked a written procedure to set up and test machines, the lab’s technical director testified.

The justice hearing the case, Robert A. Brennan, said the lab could not prove that it had followed a “scientifically sound methodology,” and in 2017 he threw out all of its breath test results from 2012 through 2014.

That was only the beginning.

Lawyers soon discovered that the lab had hidden records of hundreds of failed calibrations.

The discovery provoked a state investigation that blasted the lab’s leadership for “serious errors of judgment.”

Justice Brennan later expanded his previous order: No tests from the lab were admissible until it was accredited by a national board that oversees forensic labs.

Eight years of tests — more than 36,000, according to defense lawyers — were suddenly off-limits.

Mr. Mottor’s trial finally got underway on Jan. 10, 2018.

He and his lawyer didn’t realize that his breath test was among those that had been invalidated. It remained the state’s crucial piece of evidence.

His lawyer told the court about Mr. Mottor’s shaky balance and metal-filled feet, but the arguments didn’t resonate.

The only thing that seemed to matter to the jury was the breath test.

“The .08 comes in, and to them that’s a conviction,” Mr. Mottor said. He was found guilty.

A couple of weeks later, he learned that his breath test never should have been part of the prosecution.

He asked to have his case reopened.

When Mr. Mottor’s request was granted, the prosecutor made him an offer: Plead guilty to a lesser offense, and the drunken-driving charge would be dropped.

In February, more than five years after his arrest, Mr. Mottor took the deal.

“Even the people in the clerk’s office were high-fiving me afterward,”

he said. “They were happy that it was over.”

Since his arrest, Mr. Mottor has maintained a clean driving record.

He is still paying off the roughly $30,000 he accrued in fines, court fees and legal bills.

Nearly 29,000 of the invalidated tests in Massachusetts were already used to convict drivers, state records show.

This month, the state will begin informing those defendants that they can seek a new trial, and lawyers are bracing for a flood of requests.

So are lawyers in New Jersey, where more than 13,000 people were found guilty based on breath tests from machines that hadn’t been properly set up.

Between those two states, at least 42,000 convictions are at risk. Thousands of other defendants have already been acquitted in cases that prosecutors believe they would have won if they had been able to use their most powerful piece of evidence.

And recognition of the tests’ problems is spreading.

In Minnesota, a judge ruled last year that the state’s machines appeared to be rounding up results, falsely nudging some defendants over the legal limit. (A spokeswoman for the state’s testing program said the judge misunderstood the technology.)

In Washington State, where Dräger sent its cease-and-desist letter, D.U.I. lawyers are trying to consolidate a group of cases to challenge the reliability of the state’s machines.

And in courts around the country — including one last year in Queens County, N.Y. — judges continue to toss out individual cases when questions arise about the tests’ accuracy.

“If we are going to put people in jail and punish people, take their liberties away, take their licenses away, we have an obligation to be accurate,” said Joseph Bernard, the defense lawyer who helped Mr. Mottor get a new trial and is representing dozens of others in Massachusetts.

But there is a cost. Throwing out tens of thousands of faulty breath tests will inevitably let some dangerous drivers back on the road.

“Let’s not fool each other,” Mr. Bernard said.

“I am not going to sit here and tell you that situation and that dynamic isn’t going to happen. Of course it’s going to happen.

The question is, whose fault is it?”

NY Times Article: Natalie Kitroeff contributed reporting. Susan Beachy and Sheelagh McNeill contributed research.

TELL US ABOUT YOUR CASE

Get A Fast Response

Form Submissions have a fast response time. Request your free consultation to discuss your case with one of our attorneys over the phone. The use of this form does not establish an attorney-client relationship.

The information on this website is for general information purposes only. Nothing on this site should be taken as legal advice for any individual case or situation. This information is not intended to create, and receipt or viewing does not constitute, an attorney-client relationship.